A "Lost Generation"

It is beyond contestation that certain groups suffered

disproportionately higher casualties than others, but this is

always true in war. British and Empire fatalities are estimated to

have been almost 900,000 out of approximately eight million people

who served in the military. At a personal level many dealt with

the grief of losing a loved one by cherishing their memory

throughout long periods of mourning or in a more tangible way such

as personal keepsakes. The emotions felt by those who chose this

path were quite often private and very personal. But many within

society and among the relatives of the unprecedented numbers of

missing needed something more. They found a focus for their grief

and loss in the more formal commemorative process that developed

in the years following the war and that commemorative process

seemed to dominate the public perception of the war.

During the decade of commemoration there has been an increased

interest in the many Irish men and women who served in the First

World War. There is an increasing amount of literature on the

Irish involvement in the military aspects of this conflict. There

is a limited amount of literature available about the individuals

who called the newly independent Irish Free State, home. Many

accounts detail the number of dead suffered on all sides and are

often illustrate this with a photograph of rows of headstones, or

in the case of a documentary, a panning shot across one of the

many graveyards scattered across the landscape of northern Europe.

Whatever the final number of dead may have been there was an even

greater number of soldiers who were injured or acquired a

debilitating illness.

The total number of sick and wounded has been re-assessed over

time. It is estimated that 2.3 million British soldiers were

treated for wounds, of which 7% later died and 8% were invalided

out of the service. Many others returned to full or limited

military service depending on the severity of the wounds suffered,

sometimes to be wounded a second or more times. These groups,

their dependants and those who later received war pensions in

respect of injuries or illness seem to have received less

publicity than smaller more newsworthy groups. If the war dead

were the "Lost Generation" of the early twentieth century, this

origin of this work was the idea that the wounded and sick of the

war, especially those who were disfigured or disabled could well

be considered a "Forgotten Generation".

The Data

A good deal of the available literature of those who served in the

Great War examines the psychological damage experienced by

veterans, a phenomenon then known as Shellshock or Neurasthenia,

and now more commonly referred to as Post Traumatic Stress

Disorder (PTSD). The research from which this dataset is taken is

different in that it deals more specifically with those who

suffered from what mainly physical disabilities, although this

does not mean that many veterans suffered from combinations of

both physical and mental trauma. This is a feature that will

become apparent as the data is analysed.

The research from which this dataset is taken is different in that

it deals more specifically with those who suffered from what can

be described as mainly physical disabilities. In the compilation

of official figures for disability pensions awarded by the

Ministry of Pensions, psychological conditions of all types were

categorised as diseases which meant that they were accounted for

in the non-combatant category. An analysis of the annual reports

published by the British Ministry of Pensions from 1918 to 1939

show that even at its greatest level, an average of just 9% of the

disability pensions awarded were for a psychological disorder

directly attributable to the war service of an individual. The

logical conclusion from these figures is that the overwhelming

number of pensions awarded were for physical injuries or diseases.

This facet of the story of disabled veterans of the Great War has

not been considered in as great an amount of detail as has the

story of the victims of Shellshock.

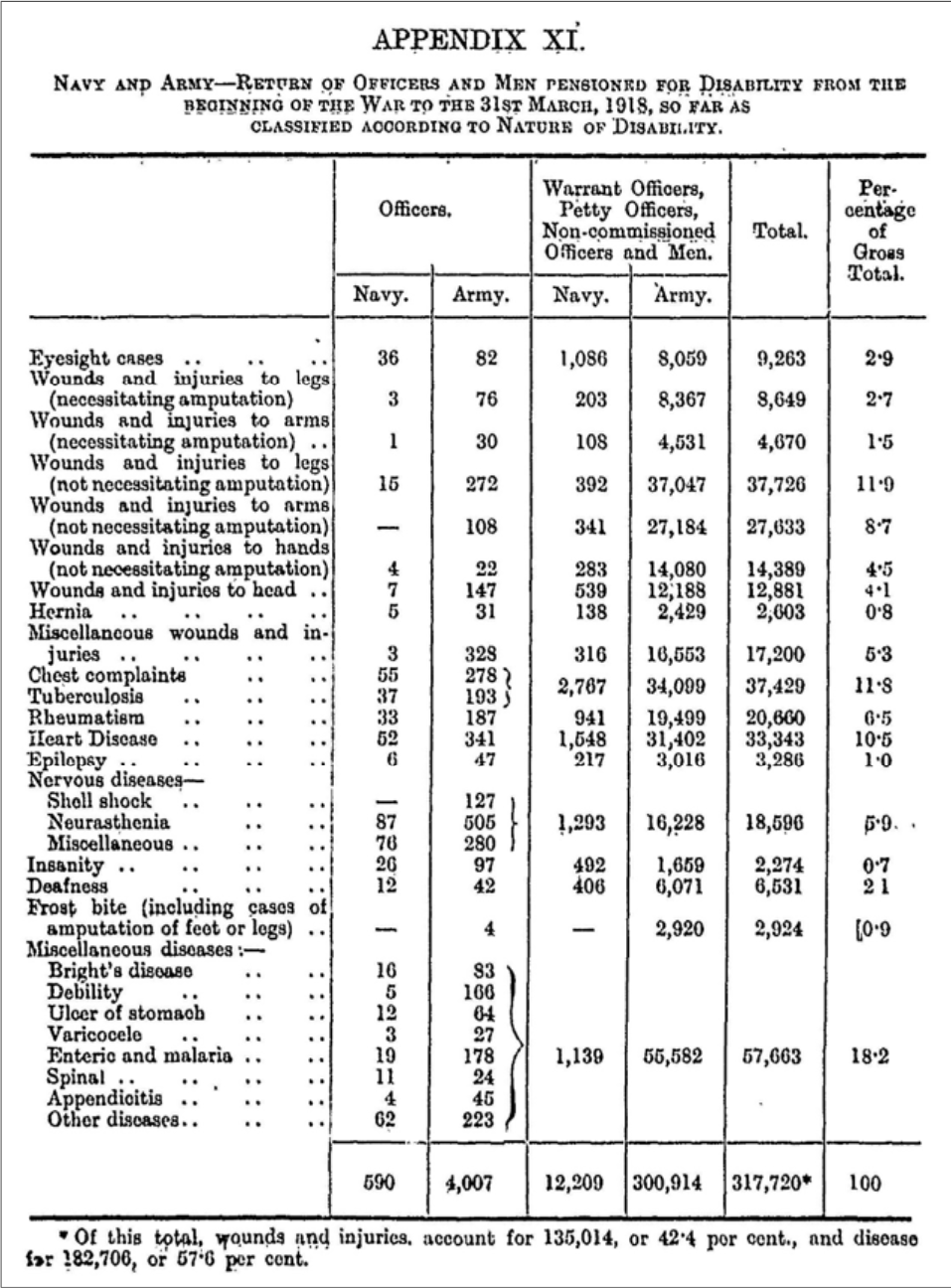

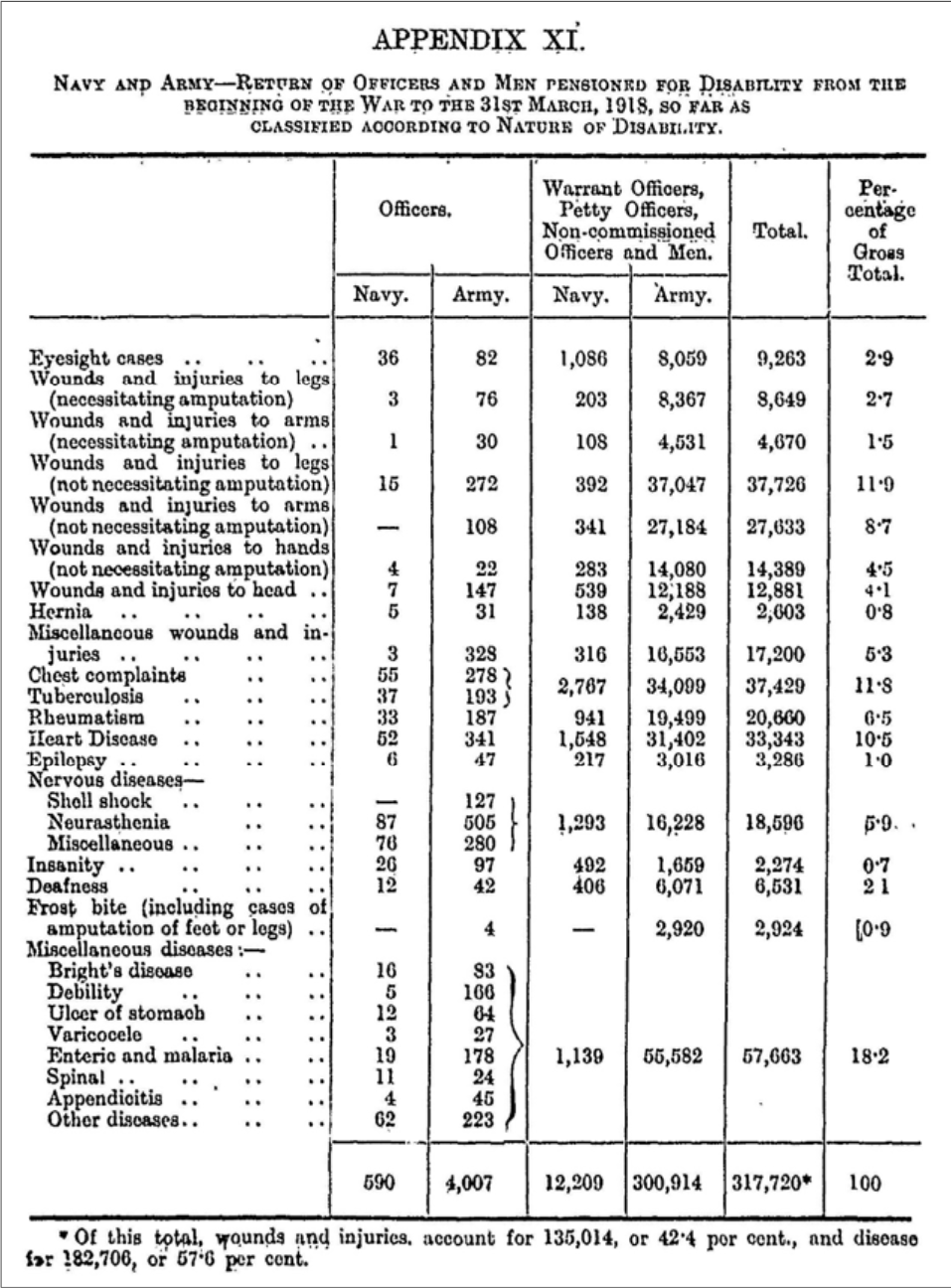

Even for example, if the statistics from the first Ministry Report

are adjusted to categorise psychological injuries as wounds, the

number of disease related disability pensions still exceed those

awarded for wounds or injuries in the proportion of 51% to 49%.

Extract from the First Annual Report of the Minister of Pensions

published in 1919.

Extract from the First Annual Report of the Minister of Pensions

published in 1919.

The Nature of the Medical Care

The British government, through its Ministry of Pensions, put in

place a three level system of care for disabled veterans in the

Irish Free State. The first level of care was provided by medical

general practitioners (GPs) who provided treatment as needed to

any veteran who was in receipt of a disability pension. The GPs

were paid for their services by the London based Ministry of

Pensions. In the early years of the Irish Free State there were

approximately 27,000 men availing of this service. British

Treasury estimates were that the cost for this was near £2.600 per

annum.

The second arm of the triumvirate of medical services available to

disabled veterans of the Great War in Ireland were outpatient

clinics. A clinic offered specialised treatment for more serious

or persistent wounds or illnesses. They could be located in either

civilian or Ministry of Pensions run hospitals. They came to be

regarded as a more efficient and cost-effective way of providing

care for veterans. During the war civilian hospitals had provided

invaluable aftercare for many sick and wounded personnel leaving

Ministry of Pensions and military medical staff free for more

immediate primary care of patients.

After hostilities ended there were concerns that disabled

servicemen were not receiving the best possible care in civilian

run clinics albeit through no fault of the hospital concerned. For

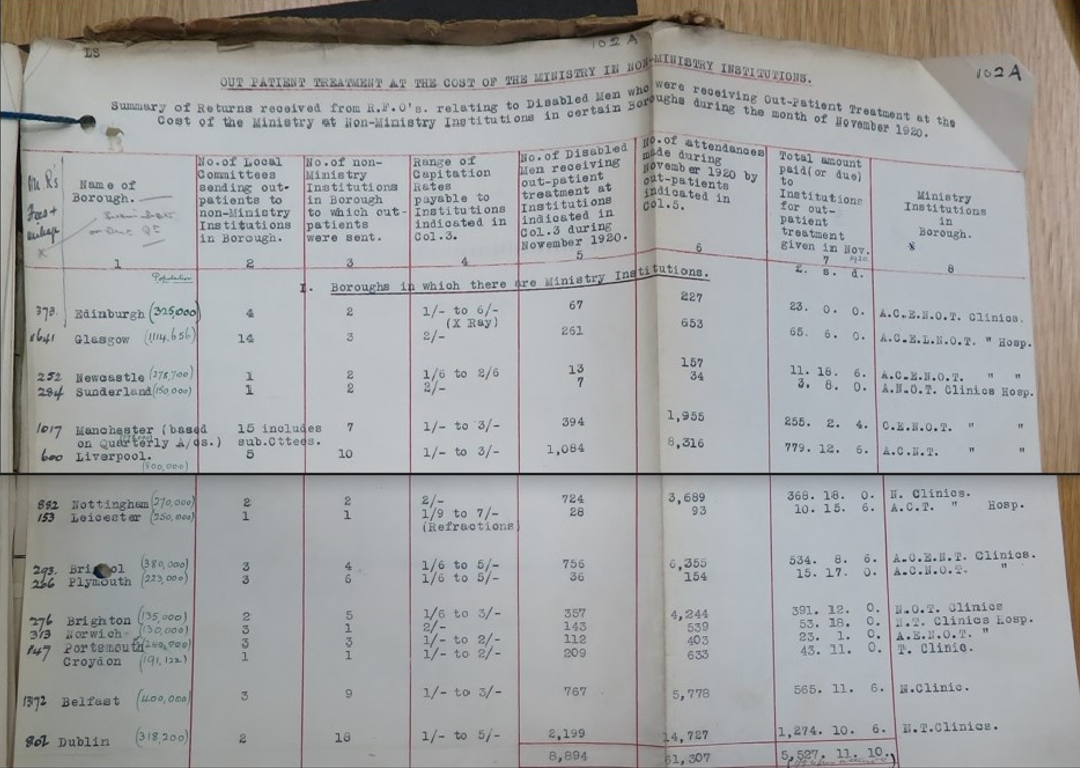

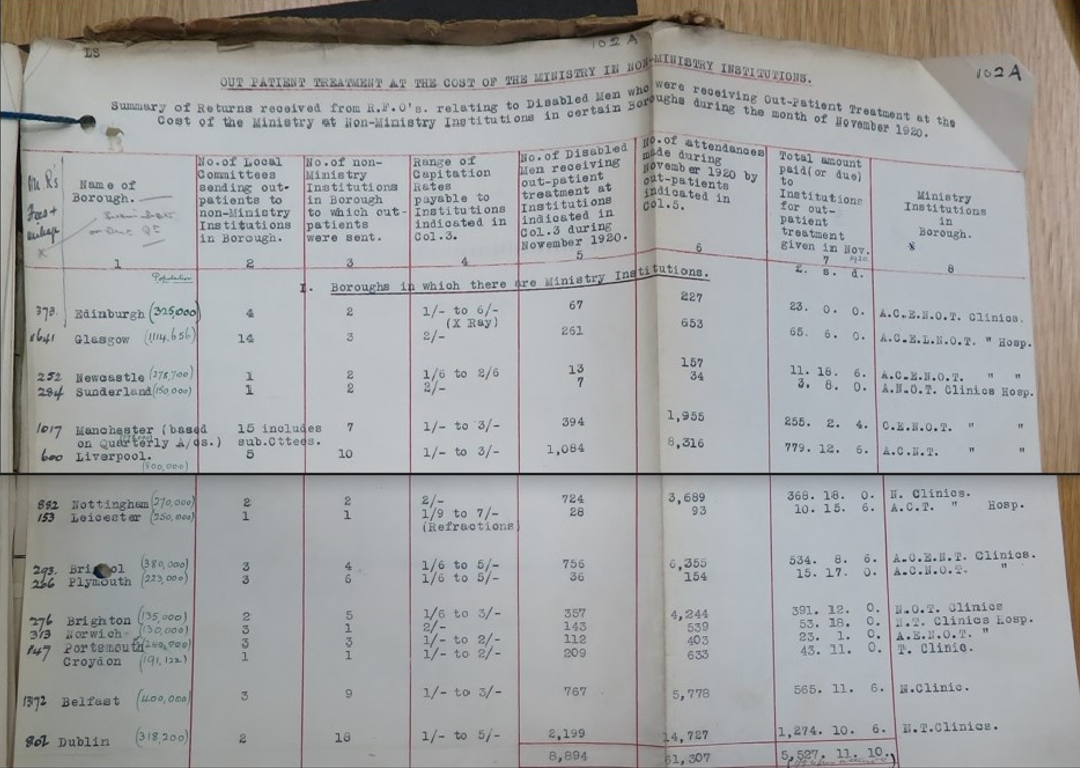

instance, in Dublin city at that time, there were eighteen

civilian hospital providing various outpatient facilities for

disabled veterans and as an example of the numbers involved, in

November 1920 alone these treated 2,199 ex-servicemen over 14,727

separate visits.

PIN15/136 Ministry of Pensions Clinics, NAUK. Extract from the

reports from Regional Finance Officers, dated 19 March 1921, of

the numbers of non-Ministry medical institutions in use during

November 1920.

PIN15/136 Ministry of Pensions Clinics, NAUK. Extract from the

reports from Regional Finance Officers, dated 19 March 1921, of

the numbers of non-Ministry medical institutions in use during

November 1920.

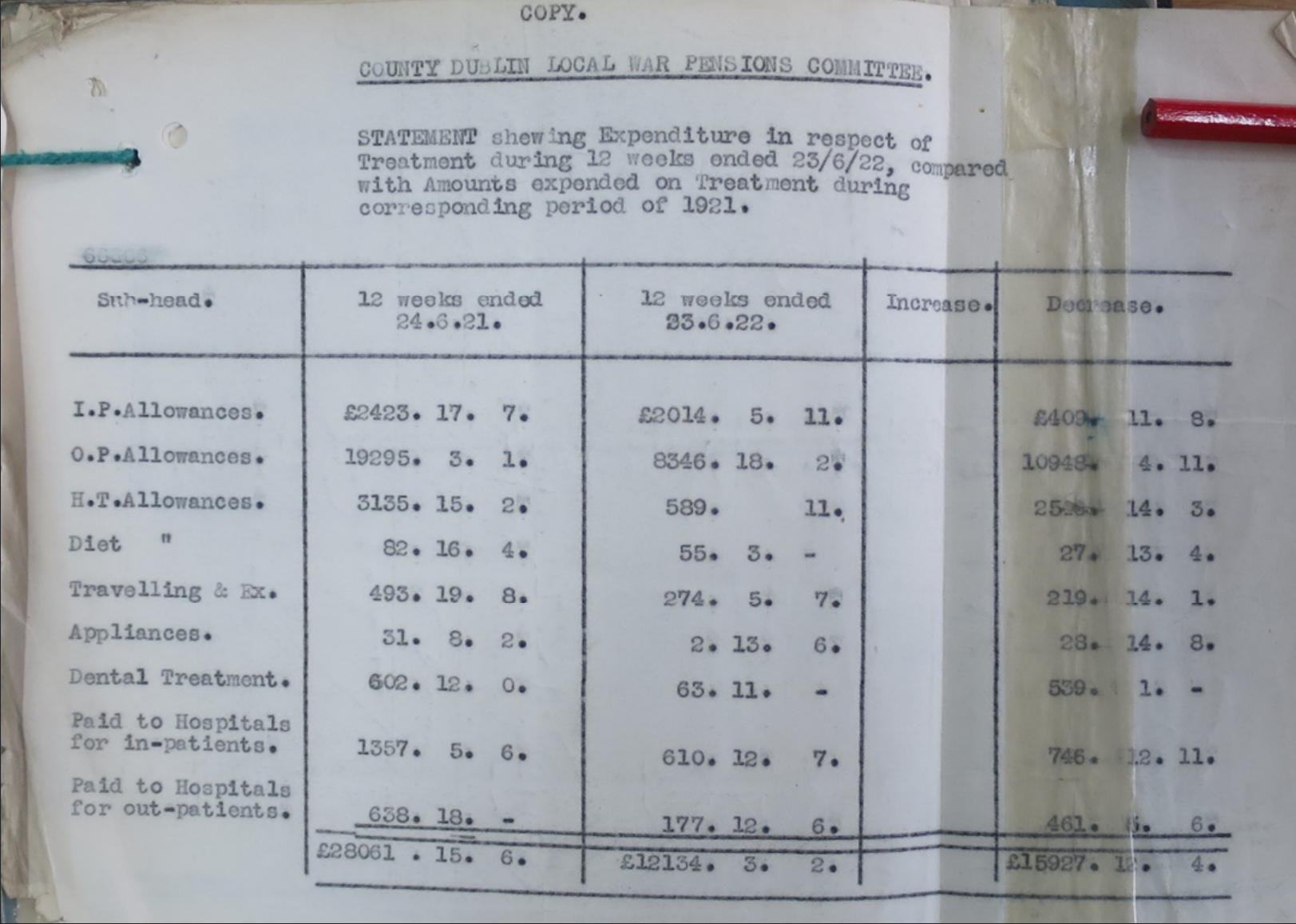

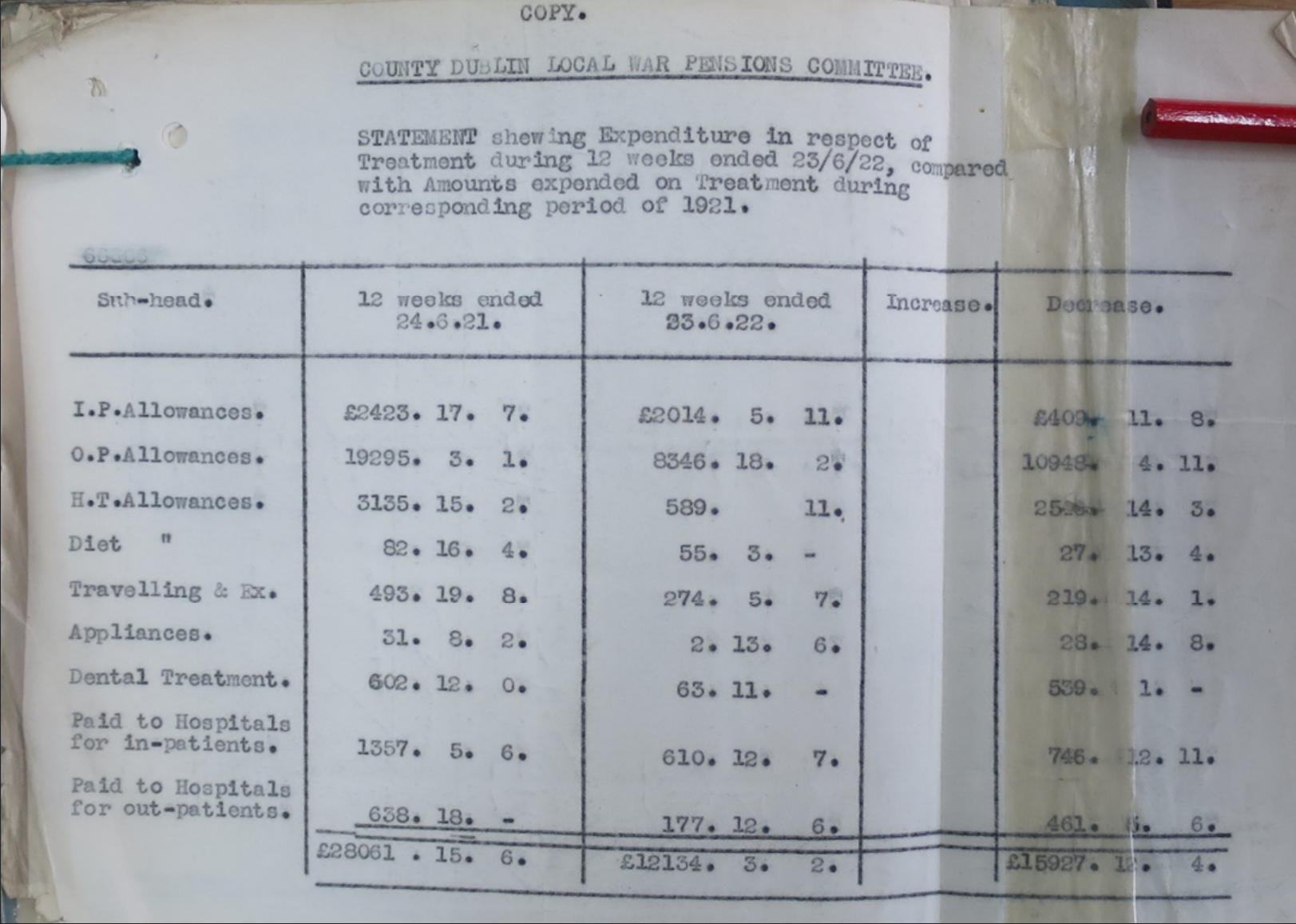

Eventually these clinics were reduced to just two Ministry of

Pensions run establishments based in Dublin and Cork, a factor

that resulted in a significant saving in the cost of continuing

medical care for veterans in the Free State. This is illustrated

in the table below extracted from Ministry of Pensions files.

PIN15/136 Ministry of Pensions Clinics, NAUK. Letter from

Ministry of Pensions Ireland (South) to Ministry of Pensions,

London dated 28 June 1922 showing the savings made by using

Ministry clinics rather than civilian.

PIN15/136 Ministry of Pensions Clinics, NAUK. Letter from

Ministry of Pensions Ireland (South) to Ministry of Pensions,

London dated 28 June 1922 showing the savings made by using

Ministry clinics rather than civilian.

The Hospital Patient Registers

In 2017, Eoin Kinsella published a history of the Leopardstown

Park Hospital as part of the centenary celebrations of that

establishment Which is located adjacent to the Leopardstown

Racecourse. It is currently a HSE facility that specialises in the

care of geriatric patients. In addition, it also provides for the

care of elderly pensioners who had been members of the British

Armed Forces. This is a legacy from when the hospital was one of

two British government hospitals in south county Dublin that had

been established to care for the sick and wounded of the First

World War.

The other hospital was the Blackrock Special Orthopaedic Hospital

that was situated on Carysfort Avenue, a relatively short distance

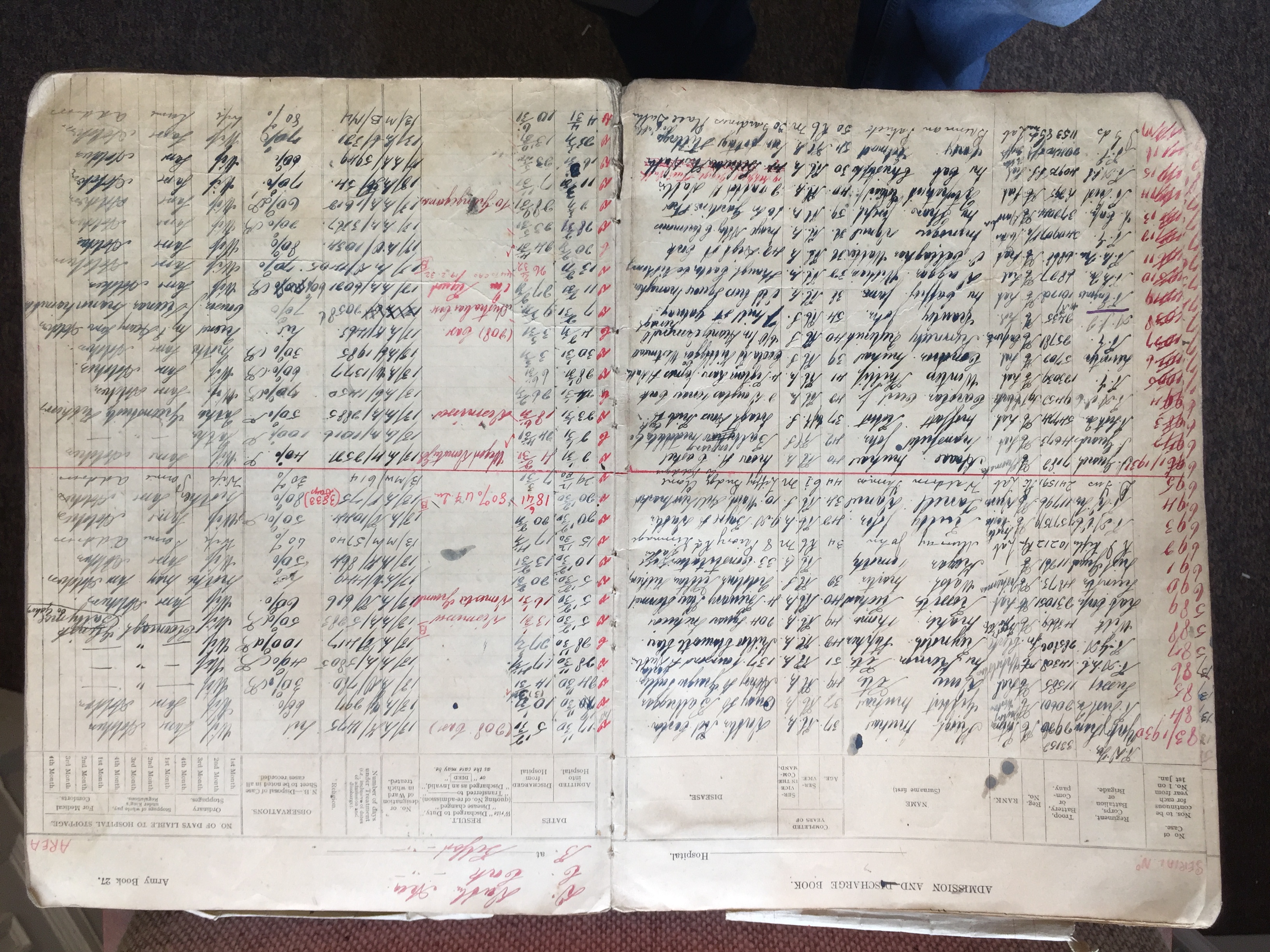

from Leopardstown. During his research Kinsella discovered seven

patient registers of First World War veterans from the two

hospitals ranging from the 1920s to the mid-1940s. Except for

Admission and Discharge Books five to seven, they are not

chronologically contiguous and as such they can be classified into

four distinct groups.

Book 1: Blackrock Admittance and Discharge Book April 1920 -

August 1926.

This book contains the earliest set of records for ex-officer

patients in the Blackrock hospital for this period that has been

found. The 286 entries in this volume also contain details of six

females who served in various branches of the nursing services who

were acquired a debilitating injury or disease as a result of

their service. As was the case then, as it is still now, the

medical treatment of officers and nurses was strictly segregated

from that of enlisted personnel.

Book 4: Colonial Chelsea Pensioners Admission and Discharge Book

May 1920 to June 1945.

Peculiarly, this book does not record actual Chelsea Pensioners,

so well known for their archaic red uniforms and tricorn hats.

Rather this book is a record of Irishmen who were disabled in the

armed forces of Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United

States. Having chosen to return to Ireland to live, their medical

care was undertaken in Ministry of Pension facilities under

reciprocal arrangements with those countries for the treatment of

British and Irish disabled veterans who chose to live in those

parts of the Empire.

Books 5-7:

Leopardstown Park Admission and Discharge Book Aug 1930 to Oct

1936.

Leopardstown Park Admission and Discharge Book Oct 1936 to May

1942.

Leopardstown Park Admission and Discharge Book May 1942 to July

1945.

These three books form the largest record of its type known to

exist in the British Isles. All told, they contain a total of

3,050 entries, some of which chronicle individuals who were

admitted on several occasions including an ex-Private of the Royal

Army Service Corps (RASC) who was a patient no less than nineteen

times between July 1928 and October 1942.

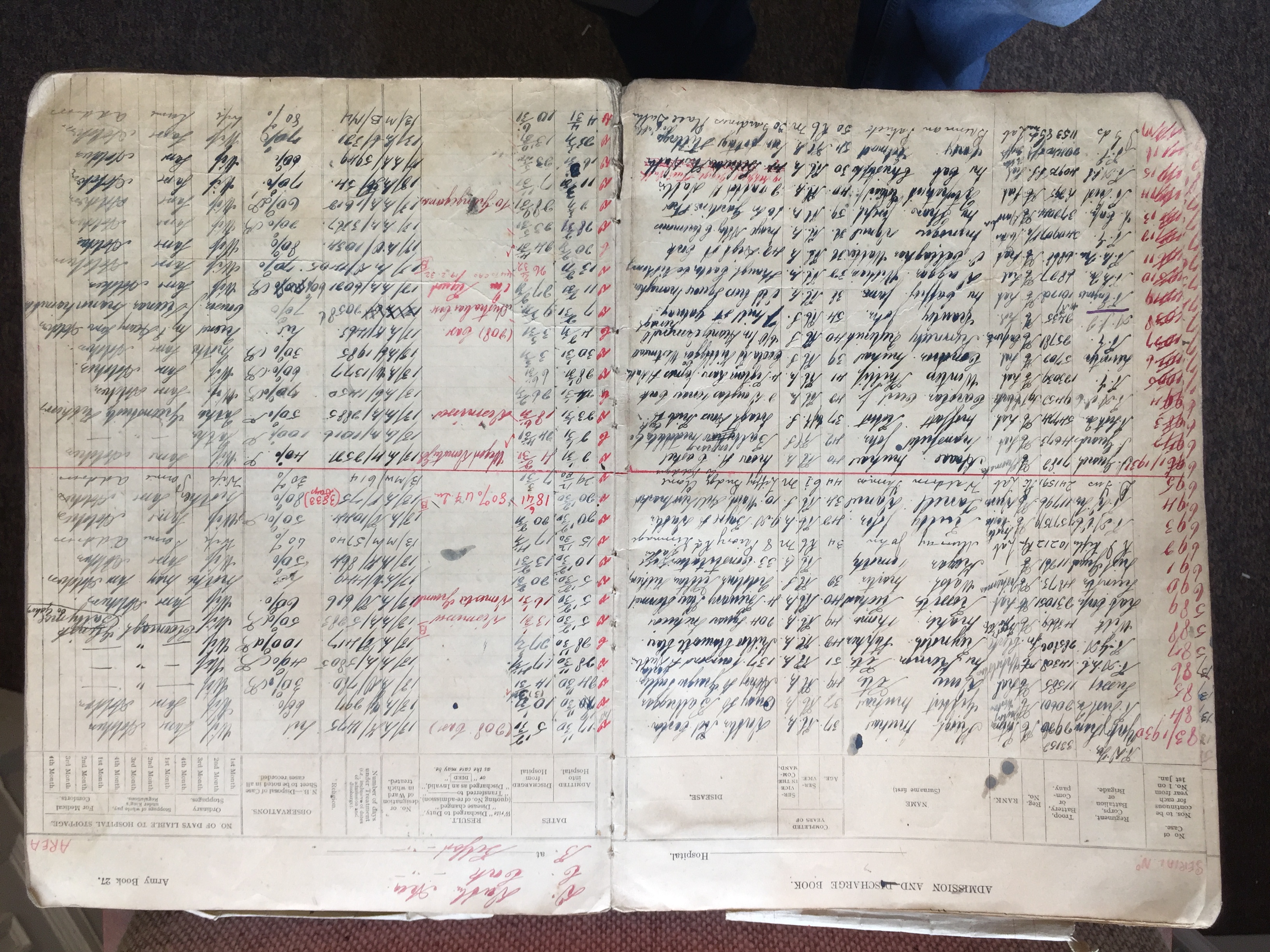

Sample page taken from one of the record books.

Sample page taken from one of the record books.